In last month’s article, Chris Nickson told us about Leeds Bridge, this month he tells us about the river that flows beneath it and through Leeds, the River Aire. He will be in conversation with Candace Robb at the Leeds Library on Thursday 8 June.

Unless we’re taking a water taxi or strolling by it, we don’t pay much attention to the River Aire in Leeds. Why would we? It’s simply there, grey, and serves little purpose – or so it seems. While it’s mostly empty these days, for a couple of centuries it helped secure the fortunes of the city. Small boats would be lined up three and four abreast at the warehouses to load and unload cargo. The cheapness of transporting by rail, then road, undid it as a vital highway. But in its heyday, it was as important as the M1 is now.

It’s a very natural boundary (in Saxon and Viking times it marked the line between the Skyrack and Morley Wapentakes), and like all boundaries, it needs to be spanned. There was a ford across the Aire, dating back to Roman times, then a ferry, and finally a bridge – which remained the only one in Leeds for several centuries.

The river provided the power to run King’s Mill, the corn mill that existed not far from the bottom of Swinegate, and water power gave Leeds an edge in the Industrial Revolution. Even small flows like Sheepscar Beck (which empties into the Aire just east of the city centre) played their part; its water was so clean that it was perfect for the washing and dyeing plants that lined its banks.

And when the river froze solid, as it did in 1684, the people held a frost fair on the ice, with stalls, ox roasting, games, and more. Man showed his power over nature, and relished the novelty.

But it wasn’t until the end of the 17th century that people began to really take advantage of the water. Walk along the Calls. Just before you reach Briggate you’ll see Pitfall Street on your left. Go the few yards to the river down Pitfall, as it was originally known, look down, and you can see the remains of the intake pipes for the first piped water supply in Leeds. The plant was built there in 1694.

In 1700 the Aire and Calder Navigation obtained an Act of Parliament to make the Aire navigable to the Ouse. Virtually as long as people had lived in Leeds, people had travelled upriver, in flat-bottomed craft, trading, and some passengers travelled that way. But this work on the river meant Leeds now had easy access to the coast for larger vessels. This happened just before the wool trade took off here, and certainly helped Leeds achieve dominance.

Exports, imports, it wasn’t long before almost everything was arriving on the river, and once the Leeds and Liverpool Canal opened there was, effectively, a Northern Powerhouse. The North had the raw materials and the industry, and it sent them around the world.

As much of this industry was originally water-powered, and laws were few and far between, the Aire around Leeds became heavily polluted (and yes, this was what people were drinking). Dead animals, chemicals, and, of course, sewage. As a quote has it: “The Aire below is double dyed and damned/The Aire above, with lurid smoke is crammed.” And another, about the Aire meeting the River Calder, states: “That’s why the Castleford girls are so fair/They bathe in the Calder and dry in the Aire.”

The river also became a place of innovation. In 1813, the River Aire played host to one of the first steamboats which was exhibited on the water. A century before, in 1720, almost 5,000 people – nearly the entire population of Leeds – had gathered on the riverbanks to watch a Scotsman named Robert paddle around in an inflatable leather boat. The river could offer spectacle and entertainment as well as profit.

A painting by Leeds artist Atkinson Grimshaw, Reflections on the Aire: On Strike, 1879, is remarkable simply because it shows the river almost empty of boats and an afternoon where factory chimneys tower like trees and belch smoke into the sky. A few boys are playing and a young women gazes over the water. Given just how vital the waterways were at this time, the quiet and rare solitude of this scene is very unusual.

But changes happen, inevitably. River trade declined, just as industry in Leeds became less and less. The water wasn’t used, and the buildings that lined it fell into disrepair. It was Leeds Civic Trust that first came up with a plan for the river, and while it took a few years, at least the buildings now have other uses, as flats, restaurants, bars, and club – plus a museum, of course.

Using the area beside the river is vital, but the water itself still has a role to play. Not commerce these days, but recreation. Boaters still use the canal, which joins up with the river through the city centre, and Clarence Dock is often packed with them.

And the pollution? At one point it was so bad that it couldn’t support any form of life; to all intent, a dead river. Now, though, it’s clean – yes, really. Take a walk along the bank and you’ll sometimes even spot people fishing there.

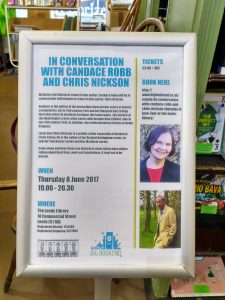

Event

Historical crime fiction author, Chris Nickson will be in conversation with historian and historical crime fiction author, Candace Robb on Thurs 8 June, 7pm at the Leeds Library.

Come along and hear these two historical crime fiction best sellers talking about their lives, work and inspirations. A treat not to be missed. More information here.

Tickets are £3.00 + VAT and can be booked here.